During the last decade, ptarmigan populations have exhibited a severe decline over large geographic areas in Fennoscandia, including Finnmark - Norway’s northernmost county that harbors the Varanger Peninsula. Climate change has been suggested as a cause for these declines as well as overharvesting and overabundance of other species (predators and competitors). However, the actual underlying mechanisms, and how management can eventually account for them, was for a long time unknown (see Henden et al. 2020 and Henden et al. 2021).

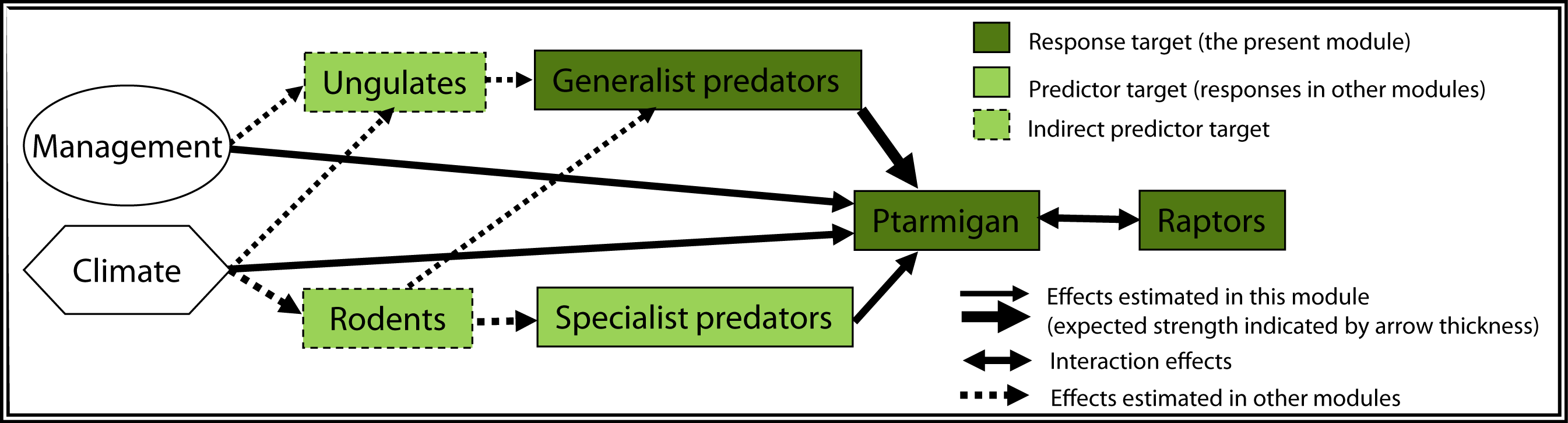

A big research challenge is that sub- and low-arctic ptarmigan populations are embedded in complex food webs with many food sources, several herbivore competitors (e.g. reindeer and rodents) and three different guilds of predators; generalist (e.g. red fox and corvids), rodent specialists (e.g. stoat and least weasel) ptarmigan specialists (gyrfalcon and golden eagle). Predation rates on eggs and chicks can be temporally very high and to variable extent linked to rodent population cycles. Climate may act both directly on ptarmigan as well as indirectly through their interactions with other species in the food web.

Ptarmigans are the most popular small game species in Varanger. Willow ptarmigan hunting is predominantly conducted by using pointing dogs, while this means of hunting does not work for the rock ptarmigan. Due to the substantial population declines, both species are now red-listed as “near threatened” in Norway and Sweden. However, hunting is still allowed with restrictive bag limits.

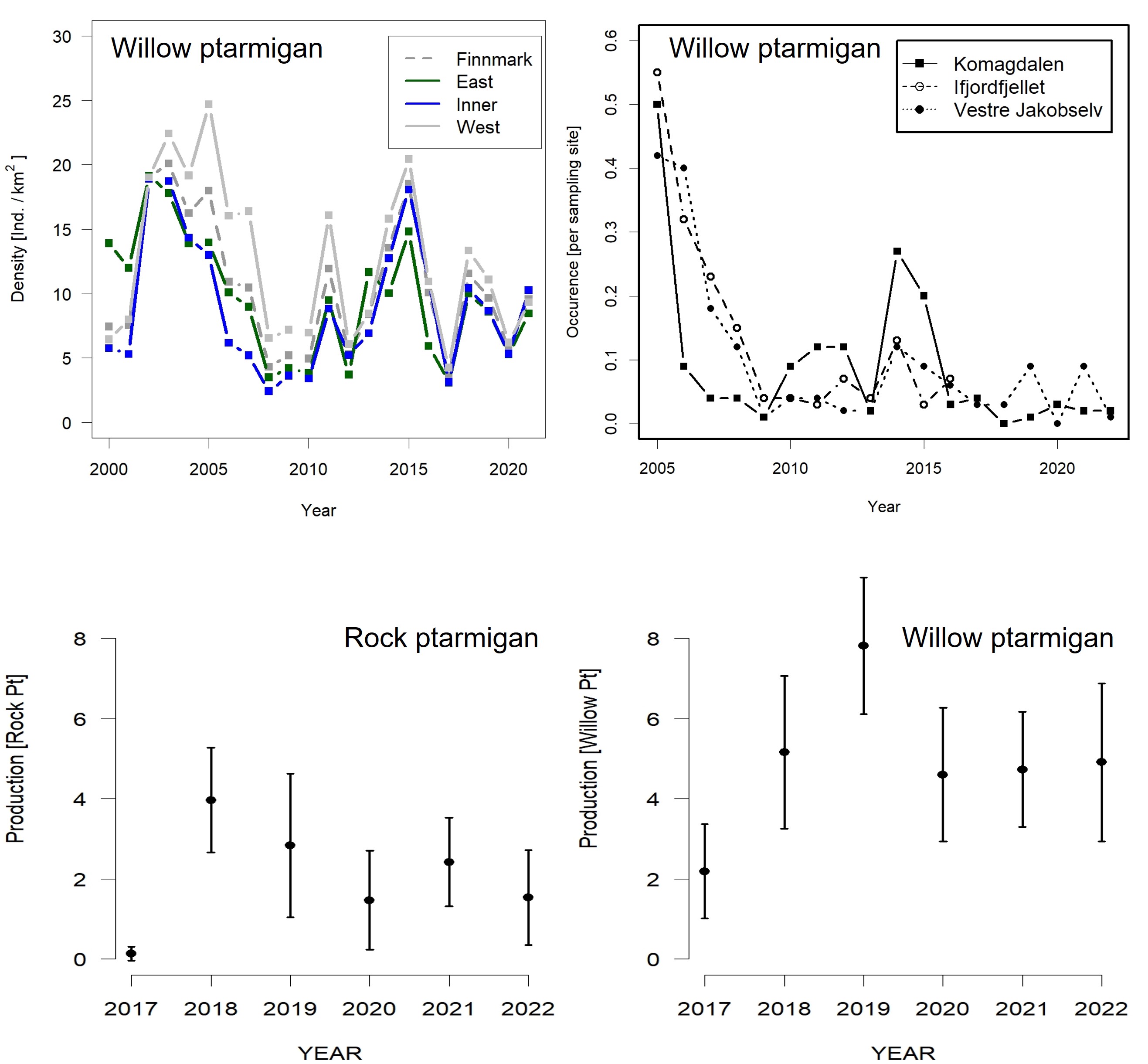

Top left panel: Shows the development in the willow ptarmigan populations in Eastern Finnmark (green line) over the last 22 years. The density estimates are based on annual monitoring, by the line-transect method, over large parts of Finnmark (through Finnmarkseiendommen). Top right panel: Shows the presence of willow ptarmigan in the period 2005-2022 on Ifjordfjellet and in two study areas on the Varanger Peninsula (Komag and Vestre Jakobselv). The data are based on counts of ptarmigan feces in permanent plots, twice a year (summer activity). Bottom panel: Shows the production (number of chickens per female) for rock ptarmigan and willow ptarmigan in a study area on the Varanger Peninsula (Vestre Jakobselv) in the period 2017-2022.

Expected climate impact

Climate change is expected to lead to warmer, shorter and wetter winters as well as warmer summers with more variable precipitation in northern Scandinavia. Increased frequency of extreme precipitation events in summer can affect ptarmigan reproductive success directly by affecting thermoregulation of newborn chicks, increasing mortality. Climate is also likely to affect ptarmigan via other components of the food web, most likely mediated through predation. Climate induced changes in both small rodents (i.e. dampened cycles) and reindeer (increased winter mortality) has the potential to influence ptarmigan negatively. Predators specialized on small rodents may switch to alternative prey (i.e. ptarmigan). Generalist predators, increasingly subsidized by reindeer carrion during winter, may cause higher predation rates on eggs, chicks and adult ptarmigan in summer. Later onset of winter and earlier onset of summer will lead to a mismatch between ptarmigan plumage color relative to the background, further increasing predation risk.

As predation appears to be the key driver of willow ptarmigan demography in Fennoscandia the model emphasizes two pathways for climate impacts on ptarmigan populations that involve predation; one works through specialist predators indirectly driven by changed rodent population dynamics, while the other is indirectly driven by ungulate carrion subsidies to generalist predators. Extreme weather events may also impact ptarmigan reproductive success directly, for instance, by inflicting high chick mortality

Management relevance

- The Varanger ptarmigan module will provide estimates of ptarmigan density/abundance for both species, but especially for rock ptarmigan, which is currently missing.

- Data on predation rates of both mammalian and avian predators will be available, as well as their presence and reproduction (breeding propensity and success).

- As causal relations between climate, harvesting and ptarmigan state is established, possible management actions could be advised and implemented. For instance, ungulate management could limit the carrion subsidies to generalist predators and control of overabundant generalist predator populations (e.g. corvids and red fox) may be considered.

Monitoring methods

Ptarmigan: We will use automatic acoustic recorders to assess ptarmigan phenology and population density in spring. We will also conduct faecal pellet counts on permanent plots (ongoing since 2005) to assess ptarmigan relative abundance and activity in winter and summer as well as surveys of the ratio of juveniles to adults in august to assess ptarmigan production. Altitudinal transects with artificial nests (both covered and non-covered) equipped with automatic cameras will assess predation risk on eggs, as well as contribute to measures of predator presence and ID (see next paragraph).

Predators: We will conduct annual surveys of a selected number of breeding sites of gyrfalcon, golden eagle, rough-legged buzzard and ravens, to assess breeding numbers and reproductive success. We will also use automatic cameras along riparian river valleys to assess activity of mammalian predators, such as red fox. Red fox data will also be obtained from the camera traps with baits used in the Arctic fox module.