Et internasjonalt team ledet av en COAT -professor ved UiT foreslår en mekanisme der de store Pleistocene -pattedyrene var avgjørende for å fremme et veldig høyt floristisk mangfold, og at en lignende mekanisme sannsynligvis vil fremme mangfold i våre samtidige beiteenger. Ideen oppstod ved arbeid med tundra -beiteenger på Varangerhalvøya i forbindelse med overvåking for COAT.

Kommunikasjonsavdelingen ved UIT har laget en populærvitenskapelig fremstilling av dette arbeidet på norsk, som kan leses på forskning.no. Ønsker du å lese vår engelske fremstilling fortsetter du under.

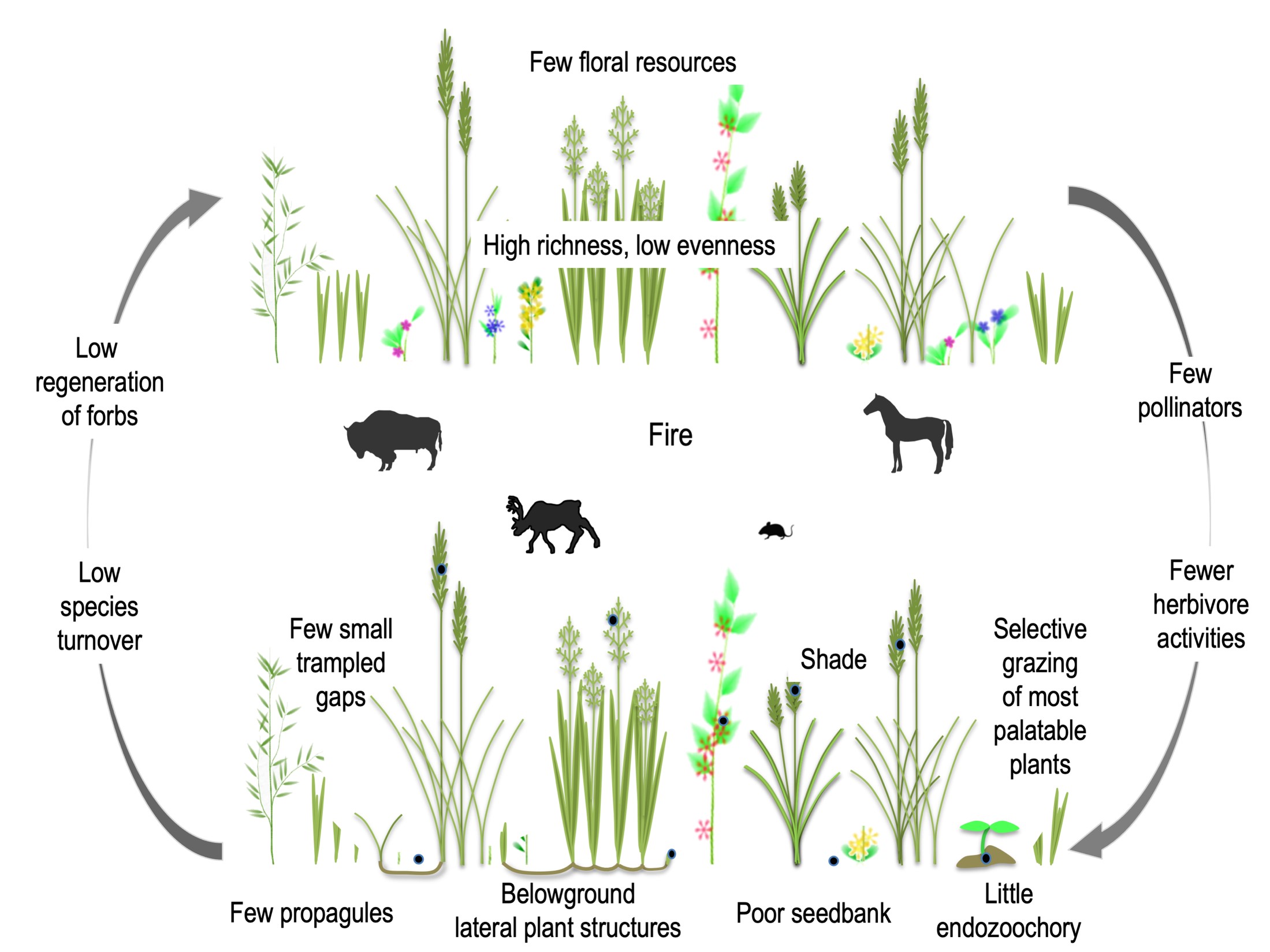

Strong plant–megafauna feedbacks in the mammoth steppe. A species-rich, forb-rich plant community with high process rates represents nutrient-rich and diverse forage for megafauna; in turn, megafauna disturb the plant community through a range of activities. Grazing and trampling increase accessibility to light: trampled gaps and litter trodden into the soil create sites for seed germination and bud bursting (solid black circles). Urination and defecation fertilize vegetation and seeds are dispersed by endozoochory (black circles in brown mound) and epizoochory. Megafauna activities may have been responsible for a substantial portion of the niche construction that occurred on the mammoth steppe.

What did mammoths, mastodons, and other large animals eat during the Pleistocene, a 1 million-year period that ended with the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago? Due to their large size, the animals known collectively as megafauna required a large amount of energy, needing food of high nutritional quality. Today we question if plants that currently form grasslands, such as prairies and savannahs, in any region of the world, dominated by grasses, could have maintained the biomass of large animals that occurred in the Pleistocene. At that time, the 'extra' nutrients was likely provided by non-grassy herbaceous plants, annual or perennial species with showy flowers that are more nutritious and hence more suited as forage for the development of large animals. These herbaceous species, known as forbs, flourished in the highly productive pastures of the Pleistocene, the so-called mammoth steppe, and are, in many ways, superior to grasses in terms of capacities such as growth rate, regrowth ability, anti-herbivore defences, etc.

Community of herbaceous plants with low presence of grasses and high nutritional value for herbivores. Photo: iStock via Getty Images.

So why are they such a minority in today's grasslands? Grasslands around the world are home to great biodiversity and include ecosystems heavily used by humans. Although dominant grasses give meadows their characteristic appearance, forbs contribute significantly to their functional, phylogenetic and specific diversity, in addition to increasing their nutritional value. However, in terms of abundance, forb species often play a subordinate role to grasses.

A recent article by Bråthen K.A. et.al. published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, led by a Department of Arctic and Marin Biology professor at UiT and COAT, Kari Anne Bråthen, proposes that the disturbances generated by megafauna provided the mechanism that these herbaceous species needed to thrive in such a competitive system, as the megafauna provided their regeneration niche. Alterations in the vegetation cover by animals provided empty spaces both above- and below ground, that easily were occupied by forbs. The disappearance of the megafauna at the end of the Pleistocene due to changes in climate and the appearance of the humans, gradually deprived forb species of the adequate areas to survive, causing dominant grasses to occupy the space and overshadowing the soil, leading forb species to lose their preponderance and maintain the secondary role that is observed in most grasslands. In this sense, the evidence obtained in systems such as current African savannahs also points this out, as there are still large herbivores that cause great damage to the vegetation and provide places for the regeneration of a high diversity of forb species. As a legacy of their past prevalence during the Pleistocene, forbs in contemporary grasslands likely still depend on the presence of selection forces resembling megafaunal activities. Greater research and management attention should be directed toward forbs to conserve the biodiversity and functioning of the grassland biome.

Weak plant–herbivore feedbacks in contemporary grasslands. Forb populations are assumed to be small and fragmentary, as they are part of the subordinate or transient species pool under strong competition from dominant species of caespitose and rhizomatous graminoids (or the occasional dominant forb). Dense, shading vegetation reduces light resources, while lateral spread of rhizomes and roots reduces belowground regeneration opportunities. Seed germination and bud sprouting (solid black circles) are reduced and the capacity of the grassland to regenerate favors dominant plant species.

Full paper

Reference:

Bråthen, K.A., F.I. Pugnaire, R.D. Bardgett. 2021. The paradox of forbs in grasslands and their legacy of the Mammoth steppe. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2405).